Dear Starlight,

It's 2:30ish am, I can see one star out my window lying in my oversized bed with too many pillows. If the star could see me, they would see me twinkling with a neck light reflecting off my readers as I finished reading Peggy, a novel by friend and author Rebecca Godfrey. They would see me gasp when I unexpectedly read my name in the quiet darkness of her epilogue and acknowledgments.

Rebecca died two Octobers ago, and Peggy, her ten-year-in-the-making novel, was completed and published posthumously this summer. Peggy was a project that moved with Rebecca throughout our time together. It was a book she brought with her through her domestic life tucked into the pocket of her imagination as she moved upstate and raised her daughter, quarreled with her husband, picked up teaching back down in the city, and enjoyed Hudson Valley apple pie and my chili.

We met over our snot-nosed, blue-eyed, roly-poly babies. She was swift to name the seeming impossibility of being what we were; artist-mother-writers. She yearned for a quick wit conversation that was not about potty training. She took a look around and decided to lasso local female talent around a bottle of wine and a book. She created a lifesaver, which we later named The Bad Book Club. Monthly, a gaggle of mostly mother-artist-writers met to discuss a book. The rules were that the book could only be female-authored fiction and primarily contemporary. Rebecca leaned on me to draw up the list of invitees as she was new to town. Rebecca was not shy to admit she wanted to curate talent, beauty, and grit. She admired prestige as she admired punk.

And so it began. Each month, there was a lighthouse calling us together, where we could and did talk about our children, but we also talked about craft, longing, surviving, sex, and our creative efforts. We read other women talk about all these things, too. Prayers between pages were written for us.

Once, about five years into our club, I suggested we make a timebox, something we each contributed to and then buried. It would be something to commemorate the us that was on the cusp of change. We got excited as we did, but we didn't organize to do it. It was an effort to do more than the three thousand things we all already did.

In the summer of 2016, I started Instar Lodge. It began simply as a place I would rent as a teaching studio for my then Creativity + Courage curriculum and workshops. It was magnificently grand and haunted with the spirit of the Odd Fellows and Rebecca's fraternal organization that had initially constructed the building. The light was resplendent, and the cedar board walls provided a constant warm scent. The wide board floors bounced when you walked, there were bees in the wall that hummed, and graffiti over two hundred years old, "I am here," scrawled on the wall. As I sat in this mighty dream space, I felt it was a space to usher in creativity and courage. I wanted it to be a place that celebrated experimentation, process, and possibility. It was so big and inviting, and I wanted to share it with my artist-mother-writer friends. I called them in.

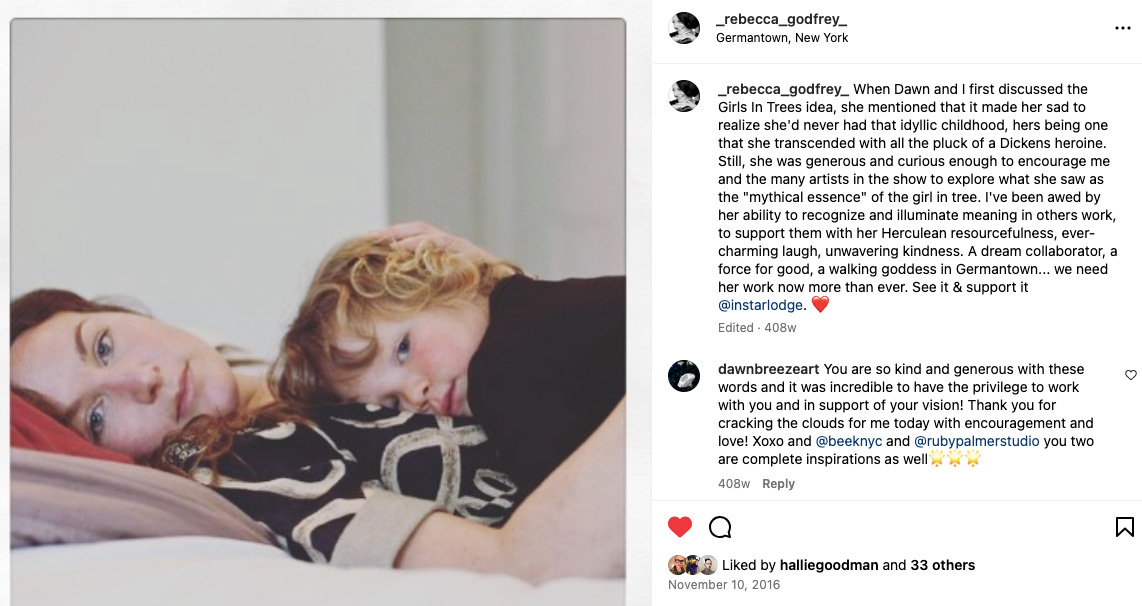

One of the first conversations I had was with Rebecca, sitting in the space in the warm summer afternoon light, which cut yellow diamonds on the butter walls. I asked her, "What do you want to do creatively that you feel is not allowed or outside the bounds of what is expected of you?"

She shared she had been noticing girls in trees and how their lithe bodies clamored up limbs to grab an apple or hang upside down, wild, unworried about their gendered position in life. She was intrigued by a phenomenon she saw patterned in her own images of her daughter as well as other friends' daughters in trees. She said, rather shyly, that she was not a photographer but still really loved the images she had captured. She said she supposed she would like to curate a photography exhibit of girls in trees. I said; "LETS!" and so that early July, before Instar Lodge was Instar Lodge, we determined that Rebecca would curate 'Girls in Trees' as the second event of Instar Lodge opening in early October at peak apple season.

We were girls in trees, not thinking of money, time, or anything practical. We scrambled and scraped our knees in fervor to manifest Rebecca's vision. Rebecca decided that not only would it be a photography exhibit, but it would have an accompanying printed chapbook of writings paired with the exhibited images…and there would be readings…and parties…and it would be unforgettable. Rebecca was feverish with unbridled energy, and like her curation of our Bad Book Club, she was immodest in her taste of excellence. She unabashedly collected her life list of A-list artists and writers to contribute to her project, which everyone did in a heartbeat.

In three months, we accomplished an extraordinary feat that was noted in the NY Times, Lit Hub, and more. I believe the power was in the permission to do something scrappy, something outside convention, something deeply personal stirring in the darkness of Rebecca's creative psyche.

As the project moved along, Rebecca asked me what I was going to contribute. At the time, no one I knew knew I was writing in the dark. I said rather shyly, as she had confessed to me her photography, "I'm thinking of writing something." And I did. And she was surprised and surprised me by telling me it was terrific. My first piece of published writing is nestled into the Girls in Trees chapbook, which features exceptional writers such as poet Sharon Olds, Nick Flynn, Samantha Hunt, and many others. Rebecca was the first person to read my "W" writing and encourage it onwards.

A year after this fete, we were in our book club, sitting in the same room as Rebecca and I had sat in, conjuring her magic at Instar Lodge. Rebecca was complaining of constant pain, and we urged her to seek emergency care as it didn't sound right. The next day, she went into the ER, and they found what she would soon learn was cancer. That day, she called me to say they told her she would need to go to Albany to do some tests. We didn't know about what. I came to the ER bringing her every printed gossip and fashion magazine I could find, and we laughed about all the ludicrous discomforts of the hospital.

Within 24hrs she learned, and we learned that she had terminal cancer. The doctor told Rebecca she had months to live, which Rebecca refused to believe and refused to allow to be true. Rebecca outlived the doctor's prediction by years. Years that were harrowingly painful. Years that she dedicated to raising her daughter and finishing her book Peggy.

Reading Peggy these past few weeks was incredible. Outside of my relationship with Rebecca and any bias I could have, the book is a joy to read. Each sentence is snappy, and the character of Peggy is a mystique. Peggy is a fictional narrative about the great Peggy Guggenheim.

Reading it, I felt like I was sitting close to Rebecca, sharing titillating gossip (she loved good gossip). Her lexicon jumped out of the pages, her favorite words like violets printed on one of her demure dresses and the cleats of her black kick-ass boots. What she did with Peggy is something she did with her one wild and precious life. She championed and shone a light on the power of the unconventional female. She cherished beauty alongside freedom and wildness. She encouraged a feminine nature, one that was feral and even a little frightening, to be honored. She was a warrior for us. Her work is now part of a legacy of literary ladies who have dedicated themselves to uplifting other untamed and undomesticated women.

I am honored to have been her friend and co-conspirator in this lifetime, and I am forever grateful for her encouragement of me and my work. As I lay there, reading her notes, looking out to the star sparkling in an ever vast sky I think this is it. We are here to love what we love and celebrate that. Our great work is uplifting and shining light on what we love.

Star light, star bright,

First star I see tonight,

I wish I may, I wish I might,

Have this wish I wish tonight.